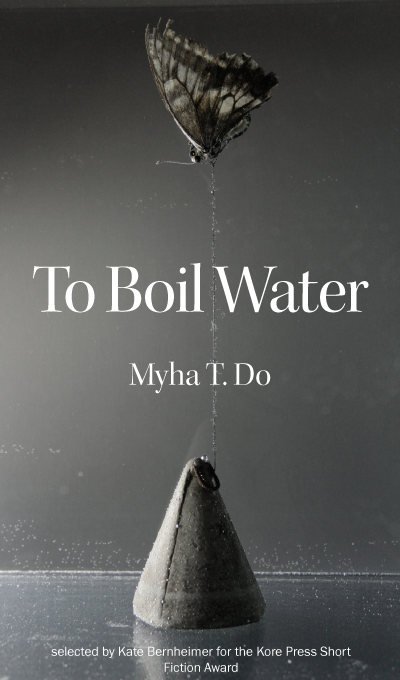

$11, 5.5 x 8.5", 16 pgs, photograph fixed

to cover, staple binding

“If you recite The Great Compassion Mantra with sincerity,” the nuns told Ching, “you can cure any illness.”

Death is inescapable; but young Ching believes that the magic of The Great Compassion Mantra can keep death at bay for her ill father. Ching grows up in a Buddhist temple, learns to recite a mantra by heart and believes, as her teachers have told her, that The Great Compassion Mantra can perform miracles.

From speed-reciting contests to her inability to boil water with chants, Ching’s relationship with mantras seems at times ridiculous; at other times, candidly sincere. We follow Ching’s journey of struggle as she comes to terms with not only the reality of death but also with her faith as well.

The narrative illuminates the agonizing fear and deep-felt emotions of loss and the only thing that Ching can hold on to: faith. Even though Ching clings to the mantra, her father’s last words continue to guilt-trip and haunt her. “To Boil Water” is a story about loss, faith and how to live in the present with an everlasting and over-looming past. |

Myha Thi Do was born in Anaheim, CA, and currently lives in Davis. She earned her MFA degree in Creative Writing Fiction from St. Mary's College of CA (2009) and is currently a PhD candidate of Comparative Literature at UC Davis. “To Boil Water” won the 2013 Kore Press Short Fiction Award, earned an honorable mention in the E.M. Koeppel Short Fiction Contest (2009) and is part of Myha’s novel manuscript, Earshot. Myha’s poem “The Lie” was published in the poetry anthology, In Other Words (2006), and she received the Jim Townsend Scholarship (2007) for excellence in creative writing.

"To Boil Water" is so iconoclastic, so elliptical and so

very mystic—I just couldn't stop thinking about it. This

story channels Yoko Ono via Franny Glass; it’s a prayer:

an occult and traditional meditation on loss that lives in

the past and future at once. I found myself reading it

over and over again, as if I myself were alive inside of

its words—this story contains eerie wisdom. I admire

the author’s direct engagement with words. The story

has a concrete, tale-like abstraction, expressed with

the handmade quality of careful hushed phrases."

— Kate Bernheimer, judge

|

|

"Myha Do’s “To Boil Water” is about our helplessness in the face of time’s wear upon the body. It is the story of the Buddhist nun Ching, who wants to save her dying father. Do’s fiction is subtle, observant, and often very funny. In this short piece Do tarries with some of the most difficult questions—what does it mean to respond to the call of the loved one? Can one accept mortality and still have faith? With time constantly propelling us forward, toward what inevitably will have been, how to live in the present?"

— Angela Hume, author of The Middle (Omnidawn)

"The rituals of life and the inevitability of death are at the forefront of Myha Do's short story, "To Boil Water," in which a young Buddhist nun does everything she believes is in her power to save her dying father. Here, hope and spirituality clash with science and fact, and what results is a story both challenging and moving. I'm looking forward to seeing what Myha Do writes next." — Lysley Tenorio, author of Monstress.

"Myha Do’s “To Boil Water” took my breath away. In it a young nun, Ching, repeatedly recites The Great Compassion Mantra hoping to stop her father’s inevitable decline. This beautifully brief story perfectly captures a daughter’s frantic devotion to her dying father and to her Buddhist faith. I’m so pleased to see Myha’s talent recognized by the Kore Prize. As one of her MFA advisors I can say with authority that there’s more where this came from."— Rosemary Graham,Author of Stalker Girl and other novels

|

Excerpt from To Boil Water

She held the bottle in her hands. It was an ordinary kind of Dasani bottle, blue and plastic. The water in it had been ordinary filtered water, but later it became extraordinary because Ching had transformed the water when she recited mantras over it. That was what the nuns told her anyway. “If you recite the Great Compassion Mantra with sincerity, you can cure any illness,” they said. Ching recited the mantra over an opened bottle of water to save her dying father. Na Mwo He La Dan Na Dwo La Ye Ye. As the water splashed from side to side in the bottle, Ching felt her heart beat hard against her rib bone.

Because of Ching’s training in the temple, she always thought that she was ready to face death, but when she heard that her father was dying, she didn’t believe it was true. In fact, she brought Great Compassion water for him and was sure it could cure his illness. Had she not heard of many people who had been saved by this mantra? Her father had told her a story about someone he knew who was saved from cancer after reciting the Great Compassion Mantra. But now it was his turn to get leukemia, and Ching firmly believed that the water she held in her hands, the water that had turned to holy water, would save him.

She wondered if Fang would recite the mantra while she was gone. No, she knew that Fang, her sister, who became a Buddhist nun together with her, would not. It was not that Fang didn’t believe in the power of the Great Compassion Mantra, but, she, like the other nuns at their temple, agreed that since Ching could recite the manta fast, Ching had it in her; she knew how to work the mantra—all one had to do was recite from the heart. Nian, they called it in Chinese. Recite.

,

|